Súai 'l Atshasa Léyerúis, il Íora Tshúkotía Fínanía

Poetry is a brain disease. Here is a demonstration of the symptoms, brought to you by a dead sceptic from the distant future, albeit before she became infamous for decrying the religious elements of her culture's self-invented social conventions.

The orthography is pretty simple; you can assume an English-like tense-lax system for accents (e.g. <ú> = /u:/ vs. <u> = /ʌ/). <tsh> and <dzh> are just /tʃ/ and /dʒ/.

The scansion for most of this stuff is dreadful and either sounded good in my head or needs severe revision.

I'll be filling this in as more are written and translated. I may even gloss some of it eventually—but be aware that the glosses are pretty unexciting.

Since many of the titles are merely the first line, I've given a more literal translation for the English ones in the title and then proceeded with a more prosaic rendition in the text itself.

The Stars Inform | Asa Atshai Altsithezeia kai |

|---|---|

| The stars say that we must have patience, that the winds will blow us safely, that tomorrow homes shall be ours. But they are merely rocks, and we are merely brave. | asan Atshai al'sithezei' kai tse' sagevara rézíretei' kai, tse' Shúthimai sampawai wash'illei' kai, tse' suntsho'ta, koisasa sin'illei'° kai. Ek' izzya vezeia kedo'hai, khé izzya veteia gal'ríhai. °siní ivilleia, 1-GEN.F.PL-be-3.PL.FUT |

| For those who have not yet heard me ramble about the history of the early Lilitai: they were space nomads, travelling between extremely isolated worlds and solar systems. This was not by choice; their old home (and the slavery that went with it) had been destroyed. Throughout most of the nomadic period, which they call the Years of the Fringe, yearning for a comfortable place to call home remained a major topic in their lyrics. | |

I saw her in my dreams | Apas sí shistoai lara trúheré, |

| I saw her in my dreams, beauty that could not be, beauty of dusty mesas and blushing skies beauty of wretched little shrubs and vile beasts but when I awoke, only the red stain lingered. | Apas sí shistoai lara trúheré, motika ts·ha alékin vezé, motika il leplí kedovasa hé keimbesheneí dazolíasa motika il vendúturí lizí regwasa hé alesturí eghilerasa ekla tsetú tshumekheré, enzí a dzherí khralíú nohella. |

| This is an example of an early ifilisúa, or longing poem, where the author describes what she misses most about her old home. While the genre is best known for delicately tip-toeing around politically volatile issues such as romanticizing slavery, early poems were more pastoral, often focusing on a comparison to female beauty, or sometimes a literal woman lost on the wastes. The most famous of these is The Garden-Haired Girl by Sarthía. | |

Can the old ways liberate? | Ostelarikai nateponezeia kin dí? |

| Can the old ways liberate? Yes, of course— they can liberate a girl from her sisters, a mother from her daughters, a heart from its head, a people from its destiny. Do not ask, child, if the old ways can liberate. Curiosity is unbecoming in an obedient fool. | Ost'ikai natep'ezeia kin dí? Zú, énzighya°— natep'ezeia kin · atetía mí'ftavin, mefísta eft'avin, amelía teksavin, stina sarv'avin. Alédzafindré, atetíê, suréú ost'ikai natep'ezeia kin. dhísúekhta natothahezríha vezé apas mí Kadzhíra. °with certainty |

| Some people were not so shy about their desire to turn to the old ways; they formed a political movement called the Mitradzhethíasa (Empire-Builders) and insisted the best course of action was to succeed the old throne. During her height, Fínanía spoke often in favour of their cause, but she was initially quite sceptical. The final words, "curiosity is unbecoming in a slave," are particularly powerful at invoking the misery of the past. | |

A machine | Mí theone |

| On another planet, a machine clicked, slowly winding its way to the end. No hand built it, no eye saw it, no heart invented it. It had no mechanism, no purpose. O, Great Winds! Blow to us a new one! Blow to us a new one. | Apas noví pléa, mí theonú kletella, wakas kekhía kewalya natotelmenella. Lenú gí zhola dústebisúla, Lenú gí tra trúisúla, Lenú gí amelía mizhanisúla. Lé gí bízikenú írella, Lé gí vekhrenú írella. Kelí Shúthimífasa! Washúthindeia sinakan surví menú! Washúthindeia sinakan surví menú. |

| A simple cry of desperation over the perceived hopelessness of their journey. The Lilitai sought to settle or co-habit more than a hundred planets over the course of their voyage, being turned or driven away in almost all cases. This perpetuated the despair that had followed them since their exodus, though it was combated nevertheless by the profound tenacity of a formerly enslaved people desperate to embrace and discover their freedom. | |

In our bed | Apas siní vúla |

| Let that for an hour more here your body we might hold, in our bed of curves and dreams, for the sky with you is finally not so empty and for once two thousand years could sound like paradise. | Rísarinrai tsenú mí taliva núis, olíes thel'-rara etanliteia kin, apas siní vúla il flovéasa hé shistoasa, kweké ts' Ossifa ýé¹ ra kaz'loíha° alviza sotanya khé míví talata, lerayerí pléovai sithizeia kin nolezyadis iv fa.² °variously: so unused, depleted, emptied, null, or worn out ¹/je:/ = íé ²literally, "no less than light" |

| A healthy Lilitu may live for up to five thousand Thessian great cycles, or about the whole length of recorded human history on Earth. | |

The coast | a Lepshúnelía |

| And though the coast bellows, its glittering calm submerged beneath the rage of suns, my heart is firm, as it shall always, my heart is firm, as it has always; a well-worn outcropping of chilled magma and ice, transformed by the cen- turies and yet always the same carved by quill-tip and wind and wave forever in your embrace. | Khé 'kla kelsithiza a lepshúnelía, liní yefameneí kelí sarokidta venavegedis venes salka il sabtina s' amelía moíha, ilú apefíta, s' amelía moíha, ilú akekhíta; mí yeloí kedova'l, soim'dí sateple hé a bedlapía, ekelara léyer- pléovanei, nýú, yetelí'té theluvíha, ekhtelara stíara hé adíanai, hé hipakanai, yeñgí talinata apas rí garsekhtýa. |

| The rocky imagery used here makes this a veiled ifilisúa (longing poem), but following the colonization of Illera, talk of geological time and the beauty of caverns would become commonplace in Lilitic verse (e.g. Illerakal by Rhetorika.) | |

While under the rain | Tsata vendilya |

| In the rain, running in the rain I saw him: that great beast of metal and heart that great civil beast who had been Master. In the raindrops, crystal mirrors, I saw the entirety, of his reason: each memory, each achievement, each touch, each savagery. But this morning, the rain fell to clarity. And in the morning, I was free. I, Íoya Chúkotía. | Tsata vendilya sivlenehé tsata vendilya lôn trúeré: el' kelí eghilera il balí amelía el' kelí eghilero swôn Oksí vishúla. Apekei diladte, lapí lemperai, trúeré yeñklativíôn, il l'í rahissai: mentí tsheñghekía, mentí dekkekía, mentí rezyekía, ment' ekkedekía. Ekla olí talata, a dilai dúpelleia lebedoshéfaka'. Khé wapas atshogía, aléponírasé, sa Íoya Tshúkotía. |

| An example of a neptifilisúa (post-longing poem). Íoya was Íora's original name prior to the Exodus; it came to be considered taboo as it was perceived as being too supine. (íoya: "respect;" íora: "warmth") | |

Don't you listen for the sound of the end of the world | Aléhaitendré a sithakal il a kekhía il a Ossa... |

| Don’t listen for the sound of the end of the world when the earth is sand and all the winds push down and our faint cries fade into the blizzard Don’t listen, don’t listen, it is not your calling. It is only the turning of the page. You shall soon again thrive. You shall soon again thrive. | Aléhaitendré sithakal il a kekhía'l an Ossa tsata hapla mokaplé·hé khé kal'pizé yeñgí shúsa khé siní vení dúteka eipho'kal natrúthiza aléhaitendré, aléhaitendré alez olawa vekhrumbedhé. stemalí lezgek·ha izzya vizé suntalya kezo-'tilidra ke. suntalya kezo-'tilidra ke. |

| Another motivational poem. Storms and blizzards are often regarded as examples of nature's power, largely because of the religious importance of winds (similar to the Greek notion of the winds of fate, albeit carried to the absurd.) | |

She Who Endured | Moiléa |

| Ten thousand years she lived powerful and brave in a tower of silk and white above even Gegloka I think it strange this queen, this grandmother was more a slave than any. What hardships she must have endured! What worries she must have suffered! At least now, with certainty Tshayéa can say she has come home. | |

| Epitaph written by Íora for the death of Moiléa Tévopía, a Lilitu who had secretly been an advisor to the king of the Ksreskézai before the extinction. The Lilitai were constantly astonished to discover how much of Ksreskézaian society their kind had actually managed, a fact that was exploited extensively by their leaders in motivating the people to build a new society. | |

A paintbrush from your head | Khristía swaval raní teksa |

| A paintbrush of your hair: For years I thought it was the last of your gifts I still had, a tiny citation in the book of my life that kept us inextricable, that kept my being incomplete unless you were included even if in just such a tiny way. But then, at last, I let myself remember all that we were all that you made me all those decades we spent as one. And I knew the paintbrush was merely a candle under our vast, starry sky. | |

| Deaths were not uncommon in the early years of space travel, as the ageing spacecraft were dangerous, nutrition was still being discovered, and there were many skirmishes. Although history does not record Íora as having lost a romantic partner to death before c. 400 LILPO when these poems were collected, such stories were hardly uncommon. | |

The one apple tree | mí Bosekhrona-lara |

| An apple tree of Alfossa of a yellow sun and a nitrogen sky of fair skin and radiant ruby kisses of such patience and a love that could last a lifetime. Carry us, your roots twisted. Take us by gene where we cannot go by wing or foot. Carry us, little branches. Take us home. | |

| An alfasúa (alpha-poem); an alternative kind of longing poem focusing on speculation about Earth. The Lilitai had no idea what their ancestors were like and could only infer a small amount of information about Terran biology from the handful of crops they had received. In one speech, Oshes Suntumekha by Gleméa Haidtúa, it is suggested that the Lilitai could be so different from other humans that they might not be welcomed "with open wings." | |

I was kissed under a stripe of passionate red | Koserasé venes mí klera dzheris |

| Kissed under a red ribbon, the fleeting banner of lust your dress thrown overhead. In my ear your breath burned. Ripe, humid with the rain of the moment to come. But from the edge of vision another storm ensnared me in the heavens outside. The beauty of the nebula brought little Fínanía to her knees and I could think of nothing else. Surely in such a home of gold-flecked filaments and icy spires one could expect to find a goddess. And then you turned and saw, and you understood, and with another kiss (after a while) you showed her to me. | |

| Admiration of the stars and nature reached a new height in the late fourth century, when the Lilitai revisited the massive Globkhro star cluster and saw the nebula there for the first time. Religious artefacts and texts from the early Sarasí period are thus heavily encrusted with suggestions that true deities, unlike their self-consciously artificial deity-concepts, might dwell within such beautiful phenomena. | |

I dreamt your after-image... | Shistoreperasé raní neptrúekhara... |

| I dreamt your ghost, I dreamed she laid beside me, pressed tight between my wings shivering so cold, so nervous shivering like I do like I did on our first time and I at once alone and together. I'll see you soon, tucked away warmly in the garden soil where we will grow old together and be happy eternally without ever leaving our bed of flowers. | |

| The Lilitai bury their dead in gardens so that they might renew the soil. The concept of the neptrúekha, while commonly translated as a ghost, is much closer to a doppelgänger, albeit one caused by grief and not bearing ill omen. | |

The lights oscillated | asa Fathíai kúgwishúa |

| The lights shook and the music pounded and together we danced what filled our hearts. I was clumsy, you were deft, but you never laughed, and I never regretted. Today, I think, I will buy a new ekhañka, with sequins and gems and glittering ribbons fine and see what fills my heart tonight. | |

| Íora was an antisocial recluse, so this is a pretty big step for her. | |

The blood-worker is a stranger | a Múnílda felozara vizé |

| The scientist is a stranger in the halls of a painted ship its bulkheads and walls alive with the playful musings of unreal tale and song. But though she may be laughed at or pitied only a fool would do so for in the shine and glitter of her curious, well-trained eye there can be seen a reflection of the cosmos itself and the greatest song of all. On this much, Lezí Regsabta and I agree. | |

| The Lilitai divided themselves into four "genders" according to aptitude. One of these, the blood-worker, encompassed everything from scientific curiosity to military valour. Despite being the engineers responsible for keeping their ship running, such women were often marginalized or ostracized by the rest of the population. It is telling that even the highly critical Íora felt a need to write about the problem. | |

Magical Quill | Haspí stía |

| If I had a magic pen I'd change this chin of mine I would edit into a gracile point and make history forget the teasing If I had a magic pen I'd melt my shoulders down And all the finest clothing then would not be so hard to find But if I had a magic pen— oh, what a chore! Not a day would go by then that others banged at our door. So maybe having a magic pen is not so right for me. Who needs it, anyway? All I truly desire is thee. | |

| Slender shoulders and a rounded chin were considered prototypical of beauty amongst the Lilitai. This poem reflects a general anxiety rather than something specific to Íora; while she had a rather strong jawline, her chin was quite narrow, and her shoulders were smaller than average. | |

Love like Victory | Amekhta dzú Sabloko |

| Bountiful Dzhemesselía blesses with apple-blossoms all who gaze upon her. But expect no fruit, young girl, for many seasons still. The boughs of true love are the hardest plants to grow. It is alright to be frustrated. Even I forget. | |

| Dzhemesselía, an annual festival in which love is either renewed or replaced, gave the Lilitai a way to condense as much relationship drama as possible into a few weeks out of the year. The results of this compression were not always favourable. | |

To mother | Oshaka abama |

| Sleepless for a decade, restless for a century; Is it any wonder that motherhood was once called mental illness? Serenity to you, Masadovía Short grows your rest. Thanks to you, Masadovía May your kind never rest. | |

| The Lilitai started off with a tiny population of only twelve hundred individuals, and did not have the necessary parthenogenesis technology to reproduce for the first four decades of their voyage. Once the baby craze took off, singers and writers took every opportunity they could to encourage population growth, but with a two-year gestation cycle, a century-long childhood, and no cultural tradition of parenting skills, the work was often discouraging and overwhelming. | |

Abandoned Soulmate | Zéa Neptedis |

| In a terrible flash, she was gone the shattered coolant pipe vapourized her not even a body to give back to the soil Yesterday had been the anniversary of the first Dzhemesselía when you found each other and stayed It was just one thin, little page separating the happiest and the saddest in the book of your life And that morning she was gone nothing left but her collar nothing left but her devotion to you Zéa Neptis, we forgive you if your heart cannot bear it all women deserve the joy that the Quills promised you Zéa Neptis, we forgive you Nurturing Poaléa forgives you Magenta-Eyed Tshayéa forgives you You may go to her Your work is done. | |

| Centuries of love, unlike the brief, lifelong relationships that humans on Earth experience, could be unbelievably devastating if lost. The brilliant engineer Deztra is said to have been the only woman to truly outlive her wife (Gleméa Haidtúa), though this can be chalked up more to military discipline and less to personal fortitude. | |

At a windy island... | Apes mí tripte shúthis... |

| On a windy island under a pale sky she was returned The earth was gritty the air salty, yet dry the sunlight faint When our shovels cracked we used our fingers scrabbling hard The dreary moon no place for Tshayéa no place for her daughters I thought once a world's greatest aspiration was to be clean But clearly now metals are not everything that counts. | |

| Reflecting on the burial of someone held dear, this reminiscence was often believed by later scholars to be about the burial of Matriarch Gleméa in 411 LILPO, as some later poets took inspiration from it, naming Gleméa specifically as the fallen. However, both her wife Deztra Salnúkzoa and the admiral Ekhessa Salnúkzoa gave a speech at Gleméa's funeral, which has survived intact, and it makes it quite clear she was buried aboard the Rokéa, in its gardens, as had Moiléa Tévopía before her. It is possible that there was no actual basis for this text and that Fínanía was simply expressing the mood left by Gleméa's death. The mention of metals is literal and refers to the constant fight to eliminate heavy metals from the water supply aboard the fleet in the early 1st century LILPO. | |

Underside of my Heart | Venelía'l sí amelía |

| Yesterday only surface things scared me things above the water The hardest thing about love was keeping up with what I was to show How I looked, how I acted— oh how my heart ached when she said "no!" But now there is no line for me to walk so neatly and I am alone The bottom of my heart has a hole in it (fear suggests this) Through which all my strength now drains from my being I think I will go back to bed until Dzhemesselía is over forever. | |

| Depression was by far the most common mental disorder among the nomadic Lilitai, affecting as much as 40% of the population at any given time and sometimes upward of 80%. While in general the task of creating cultural artifacts, customs, and rituals functioned well to manage these issues, they occasionally backfired, and Dzhemesselía had quite an unpleasant underside for many of those who were unsuccessful in finding a partner, especially those who were, for whatever reason, unable to find themselves attracted to other women. Íora was notoriously cynical and difficult to approach, a fact that was so well-known that she was occasionally ridiculed for her melodramatic antipathy in comedies written by others. | |

The magenta glove of the dominatrix | A nethurí henwesta 'l an oksíkwa |

| Shame, say we, to she who gives her throat to the collar of another and expects no requitement But oh! How the nostalgia fills my breast as I kneel on her blushing silks and inhale the heady aromas of Wemnian spices The glove fits her hand so perfectly; so smoothly And yet, for all the complaints this strange love has been showered in I feel now no imitation no cathartic re-tracing of the past's cruel paces I feel here at peace at once Íora and Íoya both Her gloves are spun of fine hair, not skaoka-hide. Her love is something unique and nurturing something I readily forget how to live without and so I keep coming back in the tiny hours before the rest awaken though tomorrow we may be called kolemai by others for the touch of her glove I would die any death so I will simply let them. | |

| This poem caused an unimaginable amount of controversy when it was first recited in 385 LILPO, and for decades many collections of Súai’l atshasa leyerúïs absolutely refused to include it. (You can probably guess why.) Íora disowned the poem in 387, claiming it was the result of a "brief period of experimentation," (talí tala 'l arotika) much to the dismay of the estimated 10-15% of the population who secretly participated in total power exchange relationships on a regular basis. It would not be for another century that attitudes towards these activities softened and revised editions of the collection began including poem #22 again. Íora never returned to the topic in her writings, at least not officially. Íoya was her Oksirapho name (which became taboo after the exodus) and a skaoka is a large semi-carapaced beetle that can grow up to 20 inches (50 cm) in length. | |

WÊ SIO LW OU YVEIR ON SE CIERE OU ENIERJI ON RASCHNES SINGE etc. etc.

(I am not actually going to translate it, it is all Latinate and that requires Effort)

(I am not actually going to translate it, it is all Latinate and that requires Effort)

Zú, suntalya! Tôñghê, olíes a Thel'pelí-Khrímrí Stipta il Sarthía vizé.

Yes, soon! Meanwhile, here's The Garden-Haired Girl by Sarthía.

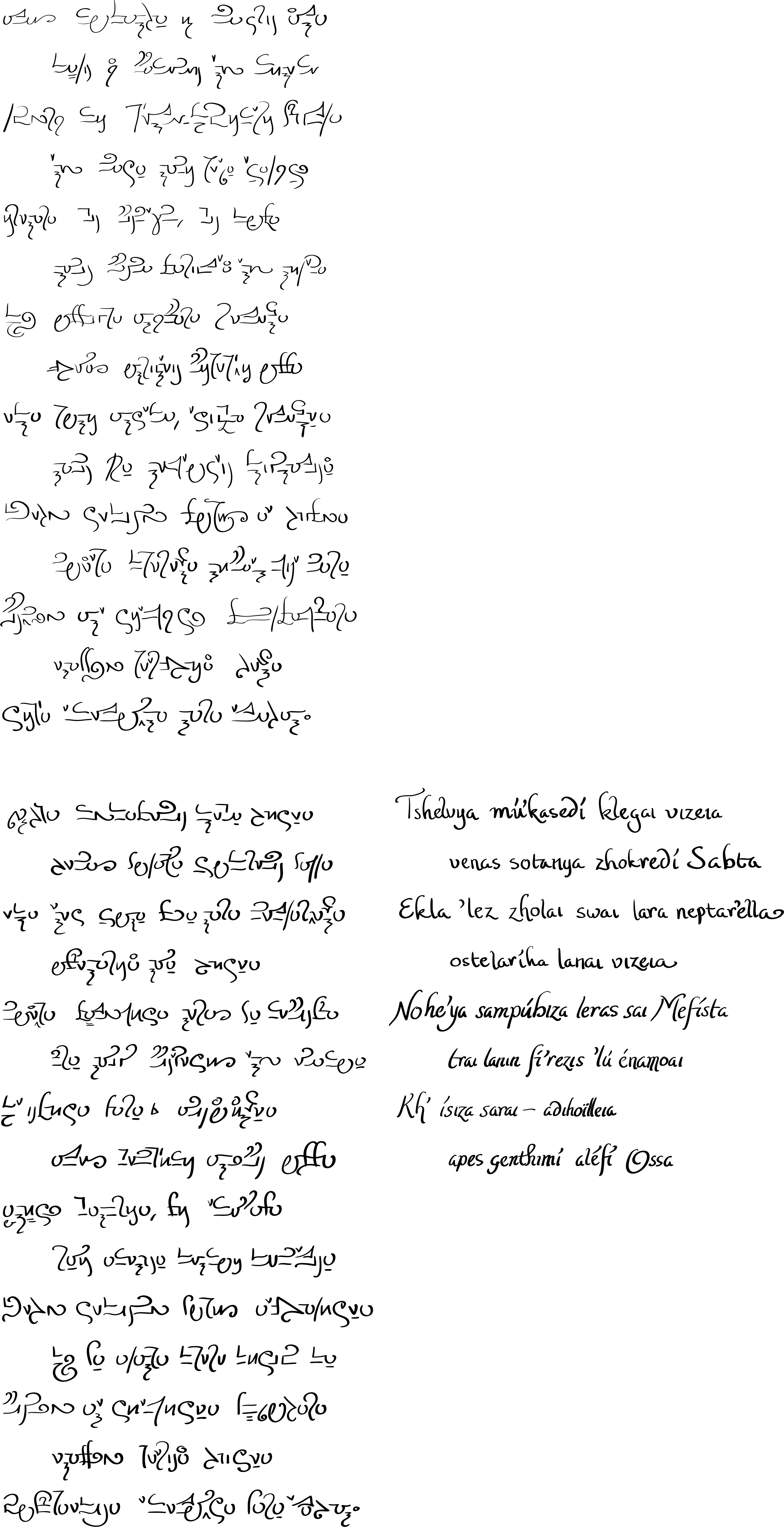

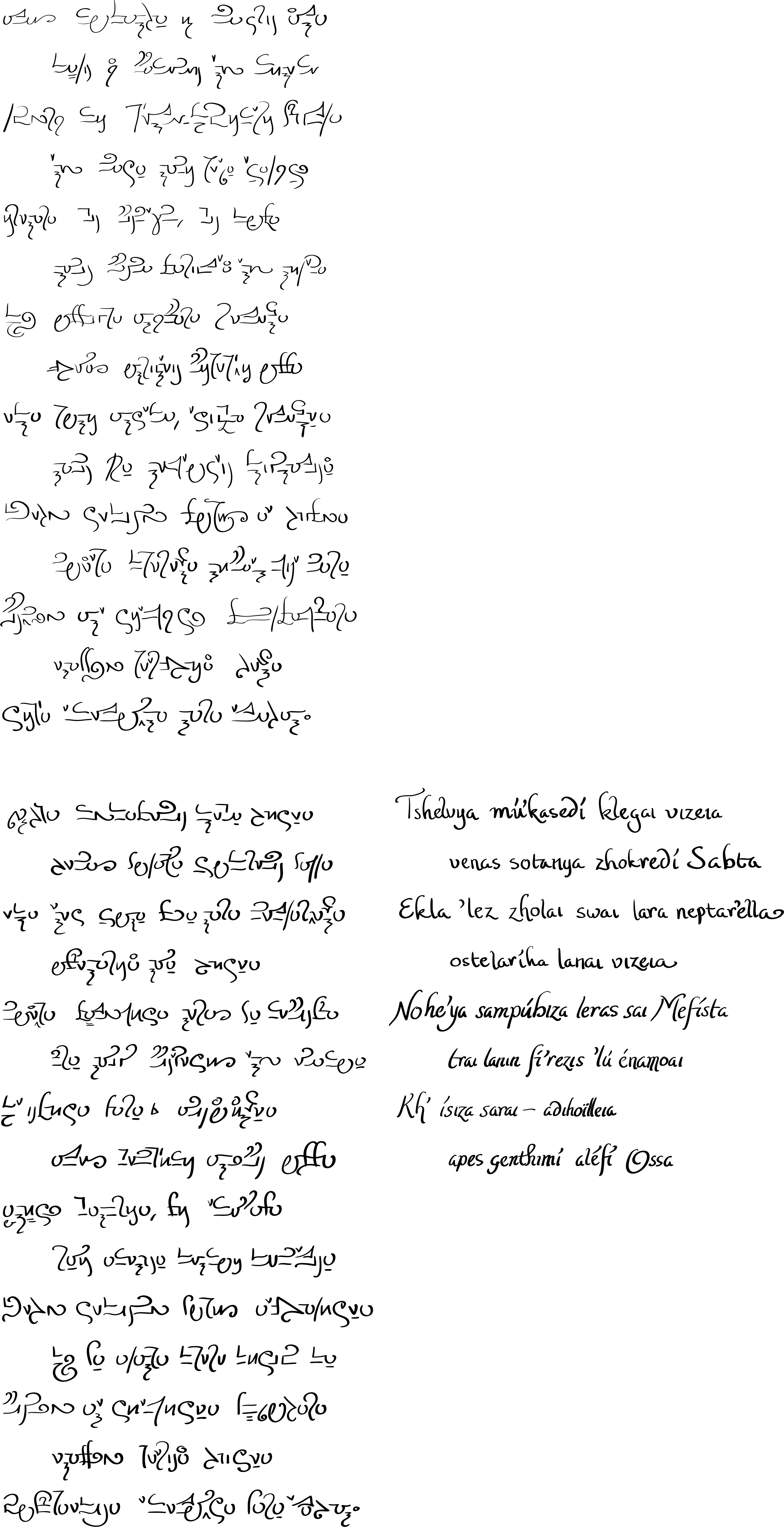

And for the complete effect, here is the verse handwritten in Títina (with a sadly incomplete transcription, but it's enough to give the idea I think.)

Yes, soon! Meanwhile, here's The Garden-Haired Girl by Sarthía.

a Thel'pelí-Khrímrí Stipta il Sarthía

| English | Sarasí | Sarasí Verse |

|---|---|---|

| In the dunes of Dashro’s sand (pure and glittering as glass) I saw a garden-haired girl (her rags torn like clouds) She had no collar, no home (her neck supple as a pear) And was surely to find darkness (beneath the hungry pink sky) But no fear or worry found her (her eyes limpid emeralds) For the past had not been kind (she rubbed still at her wrists) Despite not placing trust in tomorrow (exhausted though she was) Serenity lavished her from within. Lost long now are her bones (under the shattered sun) But not the hands that saved her (far more ancient are they) The Mother still watches/will watch over us (her eyes white as salt) And bids us to breathe onward (within the cold black sky) Have courage, my sisters (your hearts sturdy diamonds) For the past has not been kind (and we may never stop rubbing) Despite not placing trust in tomorrow (exhausted though we are) Rostyaëkía lavishes us from within. | Apas mokalvai il Dashrí hapla (kantí hé fameneí ilú mileme) Trúeré mí thelepelía-khríméurí stipta (ilú atshisai laní yeletshai kerekazhatézhé) Írelara yolí fídoséôn, yolí koisa (laní fída sarippíha ilú litona) Khé ossiya aléfara repella (venas a olrileneí fíyéthurí Ossa) Ekla yolí alzoka síú alenzigha lara repelleia (laní trai lebedoshéfí klinlapíhai) Kwevú zekínú sokhíhei alya visúa (noheneya kyerella lifa lí bímegnarai) Fínanéú alya zígembézé suntshovara (elasséú yereservíha vella) Zítha ameponella lara apaval. Tshelvya múrúkasedí otalata vizeia laní klegai (venas a zhokredí Sabta) Ekla alez ai zholai swai lara neptarlella (ostelaríha lanai vizeia) Noheneya sampúbiza leras sai a Mefísta (laní trai fíyérezíha ilú énamoai) Khé ísiza sarai des survanas adíhohilleia (apes a genthimí aléfí Ossa) Arlinté galuríara, saní mímeftasa (rainí amelíai kelmoí kentapíai) Kwevú zekínú sokhíhei alya vatizeia (khé sai atalya kyerekizin kai) Fínanéú alya zígembizeia suntshovara (elasséú yereservíha vizeia) Rostyaëkía ameponiza sarai apaval. | Apas mokalvai il Dashrí hapla (kantí hé fameneí 'lú mileme) Trú'ré mí thel'pelí'-khrím'rí stipta ('lú daz'ai laní ye'tshai 'zhatézhé) Írelara gí fíd'ôn, gí koisa (laní fída sarip'ha 'lú lit'na) Khé ossiya aléfara repella (venas olril'eí fíyéth'í Ossa) Ekla yolí alz'ka, 'zigha repelleia (laní trai leb'osh'í klinlapíhai) Kwevú zekínú soyis a' visúa (nohe'ya kyerella lif' lí bí' narai) Fí'néú al' zí'bézé suntsabtara (elasséú ye'rvíha vella) Zítha 'mepon'la lara'paval. Tshelvya mú'kasedí klegai vizeia (venas sotanya zhokredí Sabta) Ekla 'lez zholai swai lara neptar'ella (ostelaríha lanai vizeia) Nohe'ya sampúbiza leras sai Mefísta (trai lanin fí'rezis 'lú énamoai) Kh' ísiza sarai — adíhohïlleia (apes genthimí aléfí Ossa) Arlinté galuríra, sí 'meftasa (rainí amelíai kelmoí ken'píai) Kwevú zekínú soyis a'vatizeia (khé sai atalya kyere kizin kai) Fí'néú al' zí'bizeia suntshovara (elasséú ye'rvíha vizeia) Rostyaëkía 'mepon'za sarai 'paval. |

And for the complete effect, here is the verse handwritten in Títina (with a sadly incomplete transcription, but it's enough to give the idea I think.)

Added the Sarasí text for Tsata vendilya, a table of contents, and fixed linebreaking on some English versions to better match the Sarasí verse.

Fínaníaha édútí sarthíaha weltai pensí talai volebizé, zelvezé kai, ekla zelwidhina édútí yestalya vezé. Khé émeshí. Khé éthelí.

She can be a bit of a dreary writer at times, it's true, but life unvarnished is often dreary. And painful. And lonely.

*sesara thelepelítas lersariza*

*busies herself in the atrium*

She can be a bit of a dreary writer at times, it's true, but life unvarnished is often dreary. And painful. And lonely.

*sesara thelepelítas lersariza*

*busies herself in the atrium*

Translated Don't Listen. The first half is gloomy and tips downward gradually in pitch, but the second is more uplifting. The word "aléhaitendré" as it is repeated twice sounds a bit like a bugle call. (I'd write out notes, but once again I find my lack of musical education frustrating. And, no, I'm not recording myself singing it. It would not do the song justice and you would be left with bleeding ears.)

It works better when you have some sense of the melody, but I admit Fínanía tends to be so drenched in pessimism that what she thinks of as being world-moving is really just a drop in the bucket. I think, in general, that her love poems at least have a chance of being more uplifting succinctly explains why she tends not to look past those things, except to criticize (e.g. Can the old ways liberate?) and to dismiss (e.g. The stars inform). She was not generally a happy person, and notably pushed away friendships with both camps of politicians (Sarthía had been a childhood rival/friend but attempted to amend things after the exodus, and Kona il Mitrajethíasa tried to make her an official speech-writer of the movement) by writing scathing criticisms of them. Like many great writers, however, her barbs were not enough to dissuade fame, at least some of which came from her habit of taking up controversial perspectives. Nor were they enough to dissuade others from trying to love her, though the relationships were short, and ended on generally messy terms. Of course, buried underneath all of this resistance is the artist's inevitable desire to be acknowledged and recognized—she wrote in contemporary dialects and continued to submit her work for publication, and tended to be a lot more affable at parties, where she swiftly and invariably got herself inebriated.